Atmospheric Machines

Following excerpts from: Abbas, Yasmine. “Immersion at Mineral Speed.” 5th International Congress on Ambiances: Sensory Explorations, Ambiances in a Changing World, October 8-10, 2024.

To learn about the role performed by materials in the making of underground ambiances, students create an “atmospheric model” that enables them to understand the mechanical, physical, chemical and other inner workings of a phenomena observed at the chosen location. For example, at Barabar Hill, India, ancient builders/carvers have manipulated both the geometry and materiality of the caves to induce an atmosphere conducive to meditation. The mirror-polished curvilinear granite interiors transform the space into an inhabitable musical instrument and influence a design investigation around “resonant bodies in immersive spaces” (Robinson, 2020).

To learn about the role performed by materials in the making of underground ambiances, students create an “atmospheric model” that enables them to understand the mechanical, physical, chemical and other inner workings of a phenomena observed at the chosen location. For example, at Barabar Hill, India, ancient builders/carvers have manipulated both the geometry and materiality of the caves to induce an atmosphere conducive to meditation. The mirror-polished curvilinear granite interiors transform the space into an inhabitable musical instrument and influence a design investigation around “resonant bodies in immersive spaces” (Robinson, 2020).

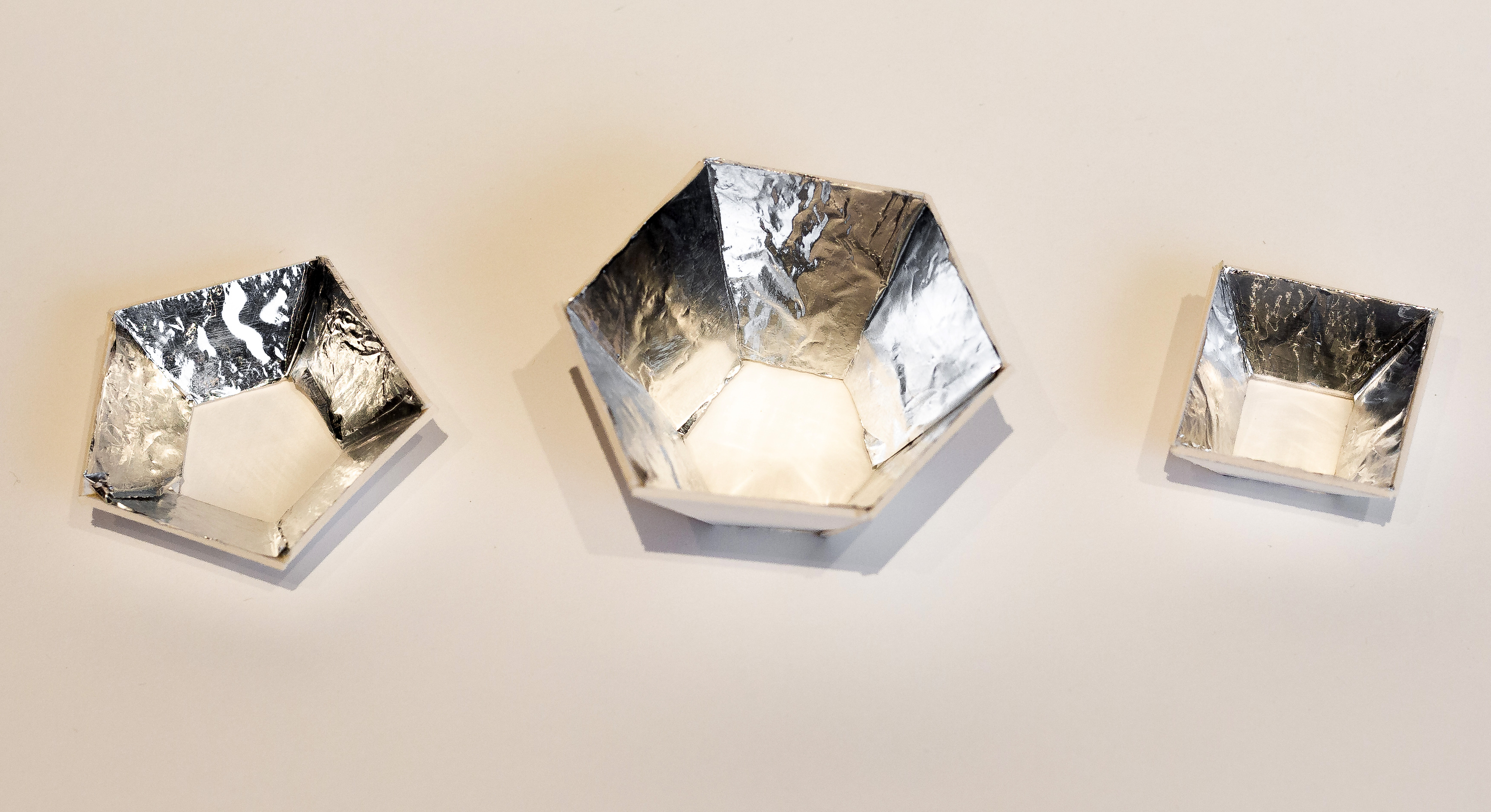

Students have empirically examined the sensation of airflow, how “granite cries” (as described by Richard Sodeinde, Fall 2023) meaning how sound reflect off materials depending on how it is polished or geometrically carved. They have explored how the earth texture captures light or smell, how water travels through spaces producing mirror effects, drumming sounds, or again how stalactites and stalagmites form. Students think through material æffects as they experiment with making atmospheric machines that illustrate, if not demonstrate, how the phenomena work in space (figure 2). Making, as Ingold has argued, is a way of embodying the life flow of materials, to understand the fluid relationship between makers, objects, and their environment, and how they influence each other (Ingold, 2010).

Hejun Cai + Chenlu Zhu, Overflow – laser variations through sound vibration, Mixed media installation, Penn State, Fall 2019.

© IMAGE H. CAI + C. ZHU

Jiayao Tang + Yuhang Hu, Phantom Space, Mixed media installation, Penn State, Fall 2019.

Jiayao Tang + Yuhang Hu, Phantom Space, Mixed media installation, Penn State, Fall 2019. © IMAGE J. TANG + Y. HU

Fall 2019, Penn State. Kiarat Vidal Rodrigez + Rana Zarei, Mixed media installation, Breathe-in. IMAGE © K. RODRIGEZ + R. ZAREI

Fall 2019, Penn State. Kiarat Vidal Rodrigez + Rana Zarei, Mixed media installation, Breathe-in. IMAGE © K. RODRIGEZ + R. ZAREI Fall 2019, Penn State. Breathe-in prototype. IMAGE © R. ZAREI

Fall 2019, Penn State. Breathe-in prototype. IMAGE © R. ZAREI

Fall 2019, Penn State. Kiarat Vidal Rodrigez, prototype (above) and concept image (right), Reflection. IMAGE © K. RODRIGEZ

We examine the performative potentials of architectural drawings and models that bring architecture closer to landscape architecture. Overall, we demonstrate ways to design and teach for spatial delight based on a range of sensory and atmospheric parameters. [...] Atmospheric devices or models explore given anticipated phenomena in a more immediate and tactile way than drawings do. They demonstrate, for example, the combined effect of light, materiality, and reflection as in Peter Zumthor’s large-scale model for the Therme Vals [...].

The model also constitutes a “machine” through which an architect can define and present his/her own worldview [Smith, 2004: pp. 61–68] “as a thinking mechanism used in making the invisible visible” [Smith 2004: p. xxviii]. In class, models were also considered as “atmospherical devices” akin to the kinetic machines designed by Lásló Moholy-Nagy at the Bauhaus [Blume and Hiller, 2014], which created spatial effects by using light in conjunction with perforated and transparent materials to cast changing shadows on surrounding surfaces.

EXCERPTS from Abbas, Y. (2019) Architecture as landscape. Envisioning ambiances: Representing (past, present, and future) atmospheres for architecture and the built environment. 14th European Architectural Envisioning Conference, EAEA14, ENSA Nantes, France, September 3–6, 2019.

Fall 2019, Penn State. Kiarat Vidal Rodrigez, concept image (right), Reflection. IMAGE © K. RODRIGEZ

Abbas, Y. (2020) Architecture and its Double: The Expanded Medium of Architecture and Spatial Æffect. in Masson D. (Ed.), Ambiances, Alloæsthesia: Senses, Inventions, Worlds, 4th International Congress on Ambiances, pp. 226-231.

Abbas, Y. (2019) Fluid spaces, enchanted forests. In Doyle, M., Savić, S., Bühlmann, V. (Eds.). The ghosts of transparency: shadows cast and shadows cast out, pp. 299–303. Birkhaüser–de Gruyter.

Abbas, Y. (2018). Computing Atmospheres. In Streitz N., Konomi S. (Eds.), Distributed, Ambient and Pervasive Interactions: Technologies and Contexts. DAPI 2018. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. (vol. 10922), pp. 267-277. Springer.

Spring 2019. Penn State. Architecting Atmospheres – Architecture Students Work, Exhibit: Plug-in Turn-on, Hub Robeson Gallery.

IMAGE © Sara KIPP

IMAGE © Sara KIPP

Pottstown Chidren Discovery Center

The Penn State UniversityFall 2019

4th year integrative design studio Students explored the design of the Pottstown Children’s Discovery Center (PCDC), an opportunity made possible by the Hamer Center for Community Design in partnership with the Pottstown Area Health and Wellness Foundation (PAHWF). The motivation design research questions of the studio focused on key questions such as these: How can architecture contribute to children’s development? How can spatial design, geometry, building atmosphere, and ambiance contribute to “learning for fun” (Packer, 2006: p. 329).

Shiyu Tong, Roof-playground Perspective and Model. IMAGES: S. TONG

Paul Panassow, Thamer ElSalem and Benjamin Nahim, Model. IMAGE: P. PANASSOW, T. ELSALEM, B. NAHUM

Akira Hikson, Kris Soto and Linda Ma, Concept Drawing and Concept Model. IMAGES: A. HIKSON, K. SOTO and L. MA